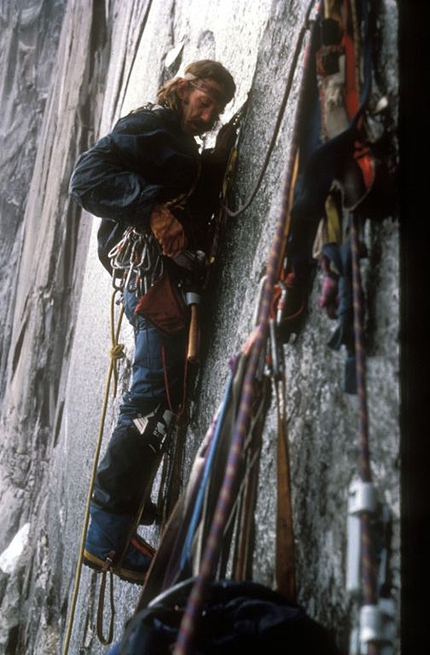

Jim Bridwell, at the forefront of climbing and alpinism since the 60's

1 / 4

1 / 4 Marco Spataro

Marco Spataro

June 23, 1975. The day after the first one-day ascent of The Nose, Jim Bridwell, Bill Westbay and John Long pose in front of El Capitan. It's the photo that represents an era. With their long hair, motley coloured trousers and waistcoats the three seem to spring from one of Kerouac’s books, from an epic trip on the road. A journey that Jim Bridwell began in the early 60s, and of which he is still a main player.

For Jim, an exceptional climber in Yosemite valley and on the world’s biggest walls, Yosemite is about "exploration. It’s about continually pushing climbing standards. It’s an adventure that began with my "discovery" of the first free ascent of the Stovelegs cracks, that then continued on the Nose with Ray Jardine". This process evolved. "Now, in Yosemite, free climbing has reached an apex, with extremely difficult routes like those established by the Huber brothers." And there are also "record-breaking speed ascents on the toughest of big walls. Dean Potter is one of the foremost interpreters of this style of climbing."

But what precisely is the trip that Jim has pursued for all these years? "My ideal climb must contain many different elements: first of all the psychological aspect: boldness, represented by the unknown and by danger. And then a climb has to mix various different skills, such as aid climbing and free climbing." The perfect route, in short "doesn’t need to demonstrate the skills of a specialist, but the completeness of the climber." An example of this is "the Salathè, which gets close to this ideal, even if it perhaps lacks a harder section of aid…"

The Salathè… that's like stating, a grande route that never loses its shine. But having said that, ",any classic Yosemite climbs are now a shadow of their former selves: in fact, Sea of Dreams originally had 39 drilled holes, now more than 200 have been added. And Pacific Ocean Wall sports 40 new holes …"

It’s the search for safety: "Yes, safety seems to have become the most important thing, but it’s unacceptable that we don’t respect what others have done before us. After all, this demonstrates a lack of respect towards ourselves ..." So one has to accept risk: "I’ve said it before: I like climbs that entail risk, even though I’m not suicidal. Climbing isn’t everyone’s game. And I don’t believe it's right to destroy the past through personal ambitions. Let’s not paint a moustache on Mona Lisa!"

But is there still the opportunity to achieve something new? "People repeat routes that are easy to get to. Now, for example, everyone is focusing on El Cap. But there are so many routes just a bit further away that are really worth repeating. Like the South Face Route up Half Dome. Or like in Alaska, where you can transfer the skills honed in Yosemite. There the climbing is really demanding and requires absolutely everything: aid climbing, ice climbing and a good dose of courage. This is the future."

While, back in Yosemite, the future "has already arrived, as I predicted a few years ago they’ve already done the first 'girdle traverse', traversing Half Dome and the El Cap. And then there’s another aspect, which I deeply respect, namely ground-up ascents, onsight, where you need to be extremely bold. One of the best at this game at the moment is young Englishman Leo Houlding. Admirable!" So there are lots of opportunities for Mona Lisa without a moustache therefore. And while we’re talking about masterpieces: "Let's not forget what Lynn Hill achieved, that young woman who managed to free climb The Nose..."

by Vinicio Stefanello

This article originally appeared in su Alp Grandi Montagne #9 Yosemite, 2002

Copia link

Copia link