New British climbs on Innaarsuit in Greenland

1 / 17

1 / 17 Ben Kent archive

Ben Kent archive

Innaarsuit was the wall’s name. Or so we were told by our Inuit friend as we heaved on the freezing Baffin bay swell in a small fishing boat. Myself (Ben Kent), Indie Fallowfield and Chris Moore were on the west coast of Greenland near the small village of Maniitsoq.

For the past 6 weeks we had sailed through storms, mist and ice 2000 miles across the Atlantic and up the coast from our home in the Lake District in the UK on a mission for unclimbed rock.

Our boat had dropped us and 100kg’s of gear and food on the small pier and sailed on two days earlier. They were bound for the North West Passage and couldn’t dally, ice was on the move and the walls of the northern reaches we were originally bound for were no longer within reach.

It was with no plan but the views from the binoculars and a heap of optimism that we hopped off and started to attempt to form a plan. No place to stay, no contacts and no transport and very little funds. After speaking to some locals who mercifully had some broken English we were soon made aware that little to no real rock climbers had ever visited the area with the intent to climb the walls themselves, rather than the summits. The rock was just too dangerous we were told. Our optimism waned... But that must mean there is rock about...

Luckily it was mid summer, daylight was constant and the temperatures were pleasant, and so many locals were out enjoying the sunshine. Over the next day or so and after much talking and debating we managed to barter a passage on a small boat with some friends we made in return for some help with a seal hunt and some painting and general labour on their lodge they were constructing on the coast around 8 miles from the village.

We searched the Fjords for suitable walls. It was June and the west Greenland coast had been battered by a colder than usual spring and so the huge towering walls and ridges were looking rather... alpine.

Massive hanging seracs and glaciers dropped right down to sea level, all the lakes were frozen. Rueing the fact that we had just approach shoes, haul bags and summer trad equipment we were quite worried by what we saw. Most objectives although feasible looked like a seriously dangerous undertaking with the kit and clothes we had with us. Especially in a place where rescue probably would not come and most of the mountains didn’t even have names.

After 5 hours or so of searching our friend had a revelation. He remembered seeing a wall out on the coast the locals called Innaarsuit. Perhaps that could be steep enough for you he mused.

It certainly was. We instantly saw the potential and decided to go for it as it was the cleanest bit of rock we had seen not guarded by neve and huge fields of scree. 400m of steep hard looking granite with very little loose looking rock and some obvious weakness lines that could maybe be linked.

And so a day later, there we were. Dropped on the shore with all our kit, a month's worth of food cooked and dehydrated diligently in the UK by Indie and a rifle lent to us by our new Greenlandic friends in case of ‘Rabid Arctic Foxes’.

Suitable camp among the vast granite slabs was found and we soon set about carrying some kit up to the base of the wall. After so much planning and waiting, the thought of just being able to go climbing was too good to miss.

8pm in the normal world would sound almost ridiculous to be setting off on a potentially 24hr+ session of on-sight climbing, but not in Greenland. Bathed in the ‘afternoon’ sun the wall looked magical and we hoped it may keep the sun until at least midnight with nothing but ocean between us and Baffin Island hundreds of miles away.

After some debate we decided on a direct line following faint cracks and grooves on the longest part of the face. Bolstering our courage with expressions of ‘we had come to push ourselves’, this line seemed the obvious thing to try despite being slightly daunting.

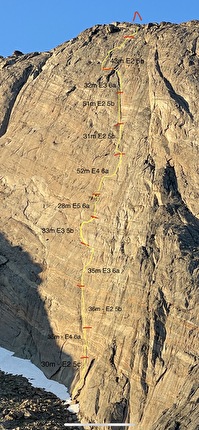

The first pitch went down easily. A small snowfield to the bottom of the wall then a fantastic 30m corner and chimney of around E2 5c climbing to a good stance, but the second pitch had other ideas. Poor Chris was suffering with a nasty cold and I'm sure he will put the first fall of the trip down to this but the fact was, it was pretty hard. A nasty bulge with some hard and wet moves prevented us from joining the next groove that we hoped held some gear and easier climbing. After one fall and a few loose holds broken away Chris managed to pull through, grading the pitch around British 6a. Getting into the hard climbing so soon was somewhat worrying considering we thought this would be the easier and more linkable part of the wall.

These two pitches had taken us over 6 hours and it was now well past midnight and so a rap down and back to camp was in order as none of us had slept well in the past 3 days. We fixed lines ready to be jugged the following day and turned in for the night at around 4 am.

Day two on the wall brought much of the same, Indie had been suffering from a cut and small infection on her foot sustained from a river crossing a week previously and so she took a rest day. Chris and I headed back to the wall to add some more pitches. The weather was perfect and we managed to push 2 more 40m lengths up the wall that included another stunning E3/4 cracked groove. Route finding was turning out to be harder than expected with the wall being so bulged that we could see little of the climbing above. A fact realised when I did a 50m pitch up what we hoped would link into the next system, only to find no gear at the top and instead a huge blank overhanging wall, resulting in a hourr lead of down-climbing back to the belay where poor Chris sat shivering and coughing. Another 12 hours of effort for just two more pitches.

We were aiming for what we thought was a large ledge, around 200m up in which we hoped we could use as a good halfway point to fix lines and set up a small camp or bivvy. Only about 30/40m separated us from our would be sanctuary but the climbing above looked harder than what had previously encountered. It was a real make or break for the line and Chris pulled out a stellar lead on our third day to pass some very bold moves up a thin groove to small ledge we had spotted in our binoculars. That was it, we thought as we quickly made ourselves busy cleaning up the belay and making the haul bag ready. We were very wrong. 2 hours later Chris hadn’t moved. A few expeditions up the blank wall below our ledge objective on nothing but skyhooks had proved fruitless and he decided to hand drill a small bolt; the only feasible way up safely was to get at least some protection before questing onwards. It was very lucky that he did as an hour later when forging onwards Chris took a huge fall when a flake and skyhook snapped. The fall, had there not been the bolt, would have been monstrous.

That was him done for the day and he brought us up to his stance and handed over the reigns. I got the short straw and teetered up for a look but ultimately decided that it just simply wasn’t safe to try and climb the remainder of the unknown pitch on just hooks. After another tense hour balancing on poor hooks painstakingly drilling another bolt to back up the pitch whilst trying not to weight them too hard I decided the moves for the next 8-10m above were now just about safe enough for me to try and I gained the ledge via much grunting and some of the thinnest friction and moves I had done in a long time. We graded the pitch E5 6a/b with the removable bolts in place. To lead it without... well we would maybe decide on that when we felt a bit braver.

The end of the pitch and resulting ledge marked day 3 on the wall and with weather coming in we knew it was our last day for a while. Sadly the ledge was not the party ledge we had hoped for, being only just wide enough for the three of us to stand on. Any camp was out of the question without some serious time-consuming faff. We packed the haul bag with all the rack on a spot we hoped wouldn’t turn into too much of a waterfall and descended the 200m back to the ground using the the entire length of our non-leading lines.

We spent the next 4 days holed up in our tents eating porridge and hoping the tents wouldn’t suddenly flood, the temperatures dropped right down to around 3-4 degrees Celsius and driving rain soaked the wall, but thankfully the rock was so clean that when the storm finally abated it took little more than 12 hours to look dry enough for another push.

A real problem faced us. We had only enough ropes to fix where we currently had a high point. Any further and we would either have to leave gear in place or re-climb the pitches if we wanted to back off for another rest. We decided with another storm potential coming in the next day or two that a summit push was the only real option if we wanted to get more lines climbed on the trip so, armed with as much food and water as we could carry, we set off back up our fixed lines for an all-or-nothing push. A point made all the more amusing as neither me or Indie had ever actually ascended any ropes nor hauled before this trip let alone first ascented on this scale. Our tiny home crags in the Lake District on which we normally climbed, although serious, were simply too small. Chris had all the knowledge with his just 1 trip ever to Yosemite under his belt, during which he also had a somewhat trial by fire experience of big wall tactics.

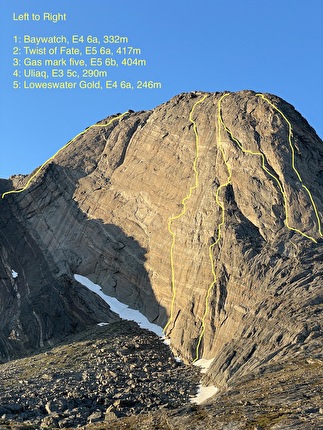

Despite this almost hilarious lack of experience we fully committed. Unlike our previous days we flew up the final half of the wall, pushing through pitch after pitch of proper 3-star climbing. 6 more pitches including another incredible 50m questing E4 pitch from Chris that we all decided was the pitch of the route. A stunning sustained 60m off-width layback crack from Indie took us within sights of the summit. As the sun set on one side and rose on the other the rolling sea mist started to make its way menacingly up the wall towards us. The weather was clearly coming in earlier than anticipated and it soon got very wet and very cold. I quickly took the gear from Chris who had led the previous pitch and started off as fast as I could up the final corner systems. It was probably one of the bolder pitches of the trip in those conditions, but I had only thoughts for the summit and just managed to reach the final summit slab and find a belay before the wind picked up to somewhere in the range of 30/40mph. Mist had completely soaked the rock and it was getting on for 7am. Indie and Chris managed to slither their way up some pretty sustained climbing with the haul bag in full waterproofs without any falls and we topped out the West Face of Innaarsuit naming the route Twist of Fate (E5 6a, 12 pitches, 417m). Sadly enjoying the views and celebrations were not on the cards due to the nearly sub zero soaking conditions and raging wind, and we quickly packed all our gear up and ran down the back of the peak in around an hour and a half to more sheltered reaches and the tents for a well-earned sleep.

Although we had completed the main objective - establish a new big line in Greenland - the climbing certainly wasn’t over. We had 3 weeks remaining and over the remaining period we managed to repeat our line in a single push of around 14 hours completely free whilst retrieving our belays and abseil line, and also put up some more lines on the fantastic West Face and South West Nose of Innaarsuit. The highlight of which for me was another superb 400m E5 6b that certainly rivalled the first line which we named Gas Mark 5’ I spent nearly 3.5 hours on the crux pitch getting completely fried and terrified in the sun whilst having the time of my life.

Our time in our small camp began to creep to an end. We barely knew the day of the month as we went in our cycle of climbing every day in the wild landscape. The water was so fresh and land so silent.

Greenland's coast had certainly exceeded all our expectations. Not a single human seen in a month, bar a few small finishing boats sailing past in the bay and what we expected to be a loose and potentially dangerous area for climbing had turned out to be just stunning. The rock was world-class and the pitches were all of terrific quality averaging around E2-E4 climbing of sustained interest with very little loose rock.

The small fishing boat honed into view as it came to pick us up at 1 am, it was almost strange to see another human again. Just in time though, as the following day snow came right down to sea level and the temperatures dropped to below freezing again. It was now August.

Our food supplies had run perfectly. All Indies amazing dehydrated Chilli’s and Dahl’s were spent and 10kgs of oats had turned into a small bag of mostly dust, great on principle but slightly boring after 25 days straight of porridge and a ration of Jam for 2 meals a day!

Although we all lost some weight and probably some sanity we had gained so much more.

We certainly felt incredibly lucky to be given the chance to experience such a place and even more thankful to the incredible locals who welcomed us into their home and with whom we are now firm friends. We will certainly be back!

by Ben Kent

INAARSUIT WEST FACE NEW ROUTES

Twist of Fate, E5 6a, 420m 12 pitches

Gas Mark 5, E5 6b, 400m 10 pitches

Loweswater Gold, E4 6a, 250m 6 pitches

Baywatch, E4 6a, 330m, 5 pitches

Uliaq, E3 5c, 290m 5 pitches

Copia link

Copia link

See all photos

See all photos