Hungchi West Face climbed alpine style by Charles Dubouloz, Symon Welfringer

1 / 24

1 / 24 Mathurin Vauthier / Millet

Mathurin Vauthier / Millet

French mountaineers Charles Dubouloz and Symon Welfringer have made an impressive first ascent of the hitherto unclimbed West Face of Hungchi in Nepal. Sometimes referred to as Cha Khung or Gyuba Tshomotse, this 7029m peak straddles the border between Nepal and Tibet and was first climbed via the SW Ridge in April 2003 by the Japanese mountaineers Kanji Shimizu, Tadashi Morita and Katsuo Fukuhara, on an expedition led by Takashi Shiro.

Dubouloz and Welfringer travelled to the Himalaya planning on attempting Gyachung Kang (7952m) which sits so "timidly" next to Hungchi, that initially the pair didn't even consider it. However, over the next five days a series of factors evolved - read complex weather, Welfringer falling ill during acclimatisation - and their gaze turned "towards this complex and aesthetic peak." While Welfringer rested in base camp for a week, Dubouloz acclimatised fully by making a three-day solo trip up to 6200m along the normal route of Hungchi.

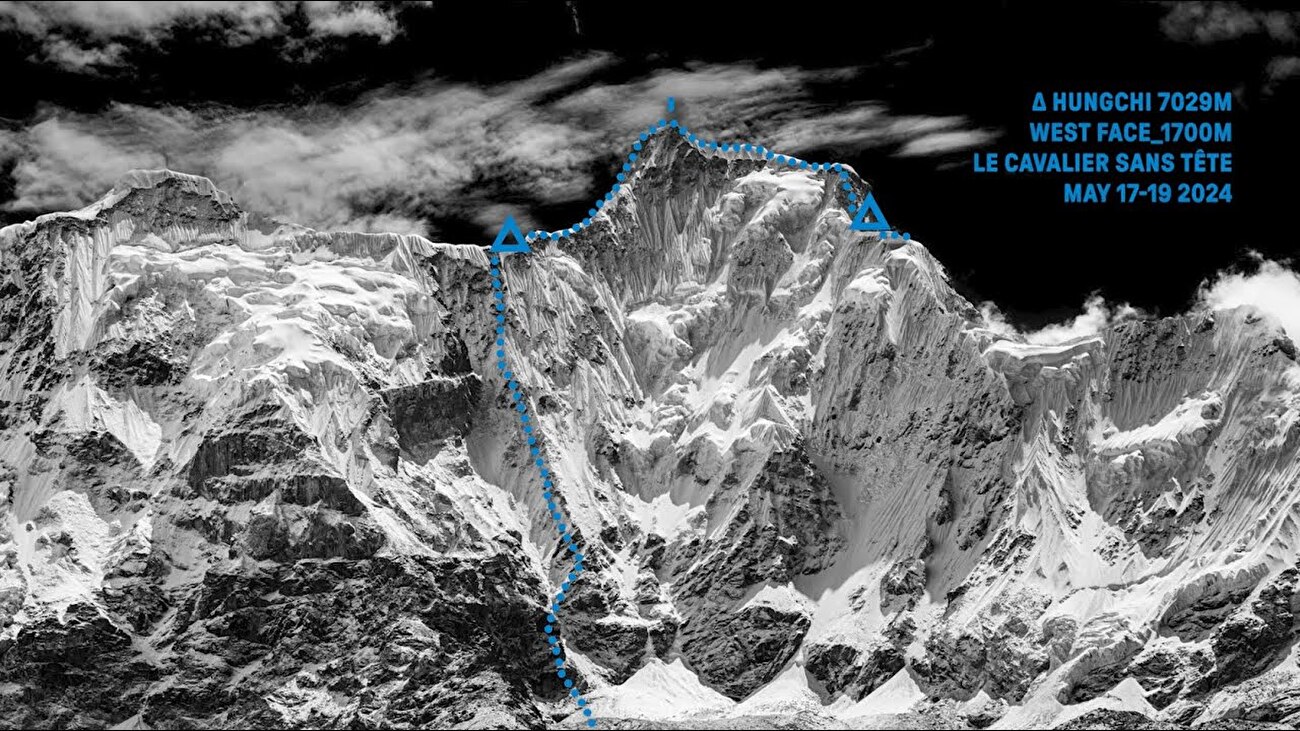

They both agreed that the West Face was an interesting objective. Dubouloz in his diary noted "There are many seracs in this face, but a direct and obvious line is drawn on the left. Then, there is a 400m ridge to reach the summit. A descent via the spur that I have just attempted would make a very aesthetic loop. On paper the plan is simple, clean and precise. It's a plan B of course, which doesn't go as high as the 7952m of Gyachung Kang. It nonetheless remains technical and motivating."

On 16 May the pair left base camp and four hours later established advanced base camp at 5300m. They set off at 5am on 17 May, aiming to climb 1300m to reach the shoulder at around 6600m as there was no possibility of a bivouac anywhere on the steep face. The climbing proved technical and although conditions were perfect - not a single cloud and no wind all day - Welfringer in particular felt the effects of the altitude. Nevertheless he persevered and 12 hours later they reached the col at 6580m where Dubouloz prepared the bivouac while Welfringer tried to regain some strength.

Dubouloz noted in his diary "We barely eat and the night is inevitably bad. Yet when we wake up, the first rays of sunshine boost our motivation and encourage us to continue the adventure. We leave for the summit. We are so trained that I admit I don't understand why we are in this state, why is it so hard?"

Only 400m separated them from the summit and early the next day, the 18th of May, despite Welfringer's advanced state of fatigue the pair pushed on. "It probably takes 6 hours to climb the snow ridge, not difficult technically but it takes a toll physically to break the trail." wrote Welfringer.

At 1:30 p.m the climbers stood on the summit but only briefly celebrated Dubouloz's 35th birthday as the wind had picked up and it was snowing. They quickly started the descent along the normal route down the SW Ridge, hoping to loose as much height as possibile, at least down to 6300m. In poor visibility and gusty winds the steep, unstable ridge proved much harder than they had hoped and at 6,700m they were forced to make another makeshift bivy.

During the night their tent broke and with bad weather forecast, the next morning they realised they had to get off the mountain as quickly as possible. They abandoned the remains of the tent to be as light as possible and then continued down the ridge but were soon faced with an extremely difficult choice, either continue down the unprotectable, exposed ridge, or abseil 1300m down the serac infested west face, knowing full-well that they had little equipment. Welfringer then came up with a third idea: abseil down the unknown east face, that appeared to be about 700m. After much consideration they opted for the "total unknown". As Welfringer lated stated "The good thing about the unknown is that it can be the worst or the best."

Thankfully this turned out to be a wise decision. The pair made about 15 steep abseils, each time finding decent ice to make Abalakov threads. "Every rapell was an absolute discovery. The anxiety of hitting a dead end was palpable. This time though, luck smiles on us.." Welfringer wrote. Finally, they reached a welcoming snow corridor. The relief was enormous as they knew that at this point they had eliminated 90% of the risks. They completed their descent into the opposite valley and then made the long return to their base camp where they were greeted by their friend and photographer Mathurin Vauthier and the rest of the expedition.

The new route has been called Le cavalier sans tête. Reflecting about their successful ascent, Welfringer stated "So much intensity over these 3 days spent up there... We gave everything, played with complex weather and a weakened physique. I'm satisfied. I need nothing more and nothing less."

Copia link

Copia link

See all photos

See all photos