Fox Jaw Cirque in Greenland, Italians traverse Baby Molar, Molar & Incisor, climb Cavity Ridge

1 / 21

1 / 21 archivio Thomas Triboli

archivio Thomas Triboli

Isolation, the search for adventure, the desire to challenge ourselves (against the odds), and pure adrenaline — these were some of the things that drove us all the way to Greenland, to experience something extraordinary and far removed from the hustle and bustle of everyday life. We wanted to experience something special, unique, and above all, real. This is how we found ourselves in this, for now, forgotten land, untouched by mass tourism.

We are Daniele Bonzi, Francesco Fumagalli, and Thomas Triboli. We met during the Mountain Rescue course, and over the years, we formed a bond that led us to embark on this shared dream to East Greenland.

Our adventure began on July 31 in Tasiilaq (the largest town in East Greenland). We were welcomed by Robert Peroni (an explorer, mountaineer, and writer of South Tyrolean origin) at his Red House, and it was from there that our adventure truly began. Separated by 70 km of navigation, our final destination was the immense granite walls of Fox Jaw Circus (Fox's Jaw).

Our base camp was 12 km from the landing point, and over three long and gruelling trips, we managed to transport 200 kg of equipment and supplies, crossing streams, moraine, and marshy areas along the river.

Daily life here is tough — there are no comforts or external help. We could only rely on our own abilities. Contact with the outside world was limited to a few satellite messages, and food was rationed. No showers, and we slept under the open sky, with an old Russian rifle as the only deterrent against wild animals.

Given the favorable weather, there was no time to rest, and after just one day at base camp, we set off for our first objective: the traverse of the Fox Jaws, which we had planned to climb over three days.

On the first day, we immediately became aware of the sheer scale of these walls. We needed almost an entire day to climb Baby Molar and reach its summit at 1,132 meters after 14 pitches. After bivouacking on its summit and enjoying the breathtaking panorama, we set off for Molar Spire. Five rappels took us down to the notch separating the two spires. From there, six pitches led to our second summit at 1,270 meters, after which we continued with another four pitches to summit Incisor at 1,360 meters, where we bivouacked for the second night.

Due to the discontinuous ridge line and obvious difficulties, the following morning, we decided to end the traverse and rappel down (15 abseils) via Tears in Paradise, a route put up in 2007 by an American expedition.

Back at camp, we all shared our thoughts, satisfied to be the first to complete the link-up of the three summits. While climbing, these horizons appeared so fragile, enormous, and wonderfully cynical. The open lands are vast, but it is the expanse of the day that surprises us the most: at this time of year, there is practically no darkness, and it gets dark for only two hours a day.

We decided to name this traverse Trident VI Orobica, in honor of the CNSAS mountain rescue squad where we first met. The route features 1,000 meters of climbing, with grades up to V+ on gneiss rock. The climbing is typical ridge terrain, with plenty of slabby sections and vertical steps that determine the difficulties. It is a completely trad route, with no gear left in situ, except for the rappel anchors already in place on the existing routes.

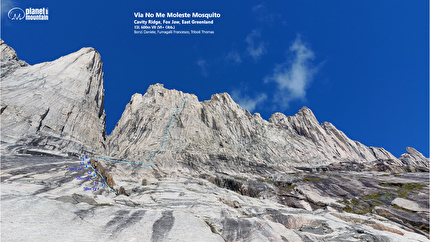

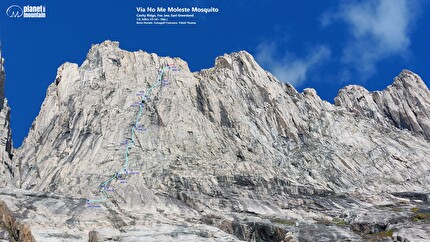

After recharging our batteries with a few days of rest, relaxation, and fishing at base camp, we decided to attempt a line on the fourth tooth, Cavity Ridge — an enormous 700-meter granite face, never before climbed by any previous expeditions. We had seen it up close while rappelling on the third day of the traverse, and after inspecting it with our binoculars, we decided on a logical line.

On the evening of August 10, we carried the gear to the base of the wall: static ropes, trad gear, pegs, nuts, cams, bolts for the anchors, carabiners, and slings. The next day, August 11, we were supposed to start our climb, but bad weather forced us to postpone our attempt until the following day.

At 3:15 am on August 12, we left the base camp in light snowfall. We reached the base of Cavity Ridge about an hour later. We racked up and, at around 6 am, began the climb, taking advantage of an obvious crack at the base of the mountain. The conditions were less than ideal — rain and snow made the rock, especially the cracks, slippery. Additionally, our heavy haul bag slowed us down significantly.

The weather cleared, and the sun warmed us, making the climb increasingly enjoyable. We progressed past corners, cracks, and weaknesses in the wall for 12 pitches and about 600 meters. However, around 11:30 pm, we decided to give up—only a few pitches separated us from the summit, but we were utterly exhausted. We all agreed to descend, and after abseiling through the night, we reached the base of the wall at 5:30 am, almost 24 hours after setting off. We returned to our tents at 8:30 am. After a celebratory cake for breakfast to satisfy our hunger, we literally passed out in the tent until late afternoon.

The route is named No Me Moleste Mosquito, after the refrain of a Doors song, and due to the countless midges (fortunately, they spared us except for the first two days). The rock is mostly good-quality gneiss, except for some easier sections. The route follows the weaknesses of the wall, exploiting cracks and dihedrals, with some well-worked slab sections. It features difficulties up to grade VII, with a mandatory VI+ section, all well-protected. Except for one bolt on the crux pitch, the route is traditional, with only the anchors equipped with two bolts, a sling, and a rappel carabiner. It spans 600 meters over 12 pitches, plus one "transfer" pitch. The rappels follow the same anchors, with an additional one between S13 and S12 to facilitate the traverse.

Though there’s a slight regret for not quite reaching the summit, we are happy to have been the first to climb the immense face of Cavity Ridge almost to its top. It was a beautiful journey, and we are grateful that everything ran so smoothly. Climbing and living in this environment made it clear to us all that we couldn't afford for anything to go wrong. Rescue operations here are rare, and the line between what happens and what could happen is very thin; even a simple ankle sprain could suddenly put us in a complicated situation.

According to Inuit tradition, the things that can make you happy in life are few and simple. Returning home after everything went so well made us feel fortunate indeed. We will always carry this land, its people, and the precious lessons it taught us in our hearts.

Copia link

Copia link

See all photos

See all photos