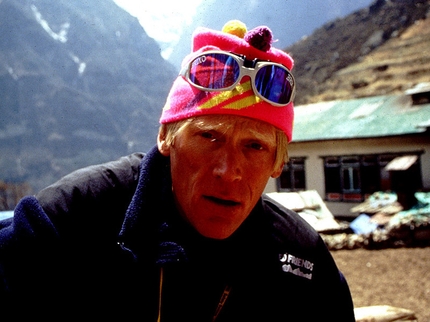

Simone Moro, from sports climbing to 8000m summits

1 / 7

1 / 7 archivio Simone Moro

archivio Simone Moro

Simone Moro, Mountain Guide from Bergamo, Italy, has a particular and peculiar background. In 1985, aged 17, he competed in Bardonecchia, the historic first ever sports climbing competition. After an extended period in the competition circuit he then moved on to coach the Italian team. At the same time he started his Himalayan relationship and was drawn to mountains further afield. His experiences with these lands and with other mountaineers, in particular Anatolij Burkreev, left a profound mark. Simone spoke to us on the eve of his departure for his great Himalayan project, the Everest-Lhotse Traverse.

Simone Moro is remembered, at least in Italy, as trainer of the Italian sports climbing team

I was the Italian sports climbing coach from 1992-96 and when I was offered the job I had 7 years competition experience which started in Bardonecchia in 1985. I specialised in sports climbing, but it certainly wasn’t the only thing I was interested in.

And before?

I was a kid like everyone else. I started climbing with my father at 13, but seeing that I made such a fuss he handed me over to Alberto Cosonni. He took me climbing and I’ll always remember how he made me second him and climb in walking boots for two years. Only later did I buy some climbing shoes and climb in other places, including the Dolomites.

How did you get into sports climbing?

In 1983 I met Bruno Tassi at Cornalba while he was hand-bolting a new route. In his own personal way he became my second instructor. He introduced me to sports climbing where the rules, in contrast to mountaineering, allow the climbers to fall. He persuaded me to take part in Bardonecchia when I was just 17. Other competitions followed and then in 1988 I joined the Italian team. Then in 1992 I was offered the post as coach and at the same time I took part in my first expedition to the Himalaya. This didn’t come out of the blue, since it was through mountaineering that I’d originally started. I wanted to dedicate myself professionally to my new job, but I didn’t just want to sit back and watch. I wanted to be “authentic” and therefore credible and respected by the athletes, because I continued to be a protagonist even though I didn’t have a starting number.

A protagonist within the Himalayan sphere...

But also at the crag, because in 1994 I climbed an 8000m peak and also an 8b. This was extremely important for me and showed that I hadn’t abandoned sports climbing, that I didn’t just train others but continued to train myself. In 1992 you would have had a hard time classifying me, because it was strange that someone who went to climb an 8000m peak still had gnarled hands and tough skin from a day out at the crag.

So when you started climbing 8000m peaks you also climbed F8b. How did you manage to combine the two?

The Himalaya fascinated me more and more and at the same time I saw climbing as a no win situation. I climbed 8a and the others did 8b, I did 8b and the others climbed 8c. It’s normal for sports to evolve, that one searches for a new result or record, but this meant little to me. The expedition to Everest opened up new horizons, even if I immediately paid for my inexperience. I discovered that altitude really does harm you. On that first expedition I suffered a form of cerebral edema because I didn’t acclimatise properly. It just seemed difficult physically. I thought that once I’d got used to the pain then it would be fine. Instead, at Camp III, I woke up one morning more dazed than usual and it was only thanks to my companions who helped me back down that I got better. There I learnt my first real lesson in sport, how behave in the Himalaya.

And since then?

I’ve taken part in many other expeditions. In 1993 the first winter ascent of Aconcagua in a day and in that same year I made it, solo, to 163m short of the summit of Makalu. In 1994 I failed on Shisha Pangma and then ascended Lhotse shortly after having climbed some 8b’s at Cornalba. In 1995 I tried Kangchenjunga unsuccessfully: during that expedition we found the body of Wanda Rutkiewicz. In 1996 I stepped up the pace and went to Fitz Roy in January with Adriano Greco – we climbed Supercanalata, ascent and descent in a day. Then I went to Shisha Pangma, again with Adriano Greco, and we set another speed record - ascent and descent with skis in just 27 hours.

1997 was important because I met Anatolij Burkreev and this changed my life, both as a mountaineer and as a man. Above all I saw him as a man who was also a mountaineer. In some ways I feel like repeating Messner’s words: “I feel lucky to have failed many times, for this means that I’ve learnt from my mistakes but also that I am alive today. There are some, however, who never failed and the first time they did, unfortunately, paid with their lives.

How do you define this interest in 8000m peaks? An infatuation?

8000m peaks have given me great motivation. I know that the race to do as many 8000ers as possible introduces nothing new to the world in general and climbing in particular. There are already 8 or 9 people who have accomplished this feat, and there will be others no doubt. But it is one thing giving something to the sport, and another giving something to oneself. I have to add that doing an 8000m via the normal route, apart from giving nothing to mountaineering, doesn’t give me anything anymore. Were I trying to do all 14, then I wouldn’t have returned to Lhotse and I wouldn’t try to accomplish speed ascents, new routes or climb in different seasons.

I would try them via their normal route, when there are plenty of expeditions, possibly with oxygen, and then I’d start collecting. But that doesn’t interest me. The fascination of an 8000m peak lies in its height. Technically speaking, it’s clear that the future lies in 7000, 6000 and 5000 meter peaks, but at 8000m you’re no longer hungry, you don’t sleep anymore, you lose your bearings, don’t know who you are or what you’re doing. Unfortunately these situations only appear in 14 zones at 8000 meters.

But why search for them?

I haven’t got an answer to that question and hope not to be able to find one, because the day I do will mean that I’ve lived and experienced all there is. Since life is a constant discovery to which the fundamental final answer can never be found. At least not like this. Mountaineering is a way for me to discover myself and these answers. One matures studying, at work, or simply living or travelling. It would be fair to say that I’m maturing, first as a man and now as a mountaineer, travelling and living there, in the Himalaya.

And what about your decision to climb the 7000m peaks in Russia…

I wanted to live and mature and discover a world which my friend Anatolij Burkreev had told me about briefly. He was no longer here and I thought that what he’d wanted to say I’d probably be able to discover there, on his homeground. This was more important for me than climbing an 8000er. I received the answers to the questions I was looking for and now I’m restarting the process to understand other things by going to do the Everest-Lhotse traverse.

I’m not after setting a record, because Messner did that and then the seven people who followed him. I’m not after fame and glory, because even though I’m one of the fortunate few who can live off mountaineering, I continue to receive confirmation that one doesn’t get rich or famous. On the contrary, my bank balance is always in the red and it’s a great achievement to be above the black line for a short period.

You like it immensely

I like it a lot; it’s given me a lot even through the sole fact that I met Anatolij. It was worth it just for that. I met him in October 1996. After a month in Base Camp I still hadn’t seen him, no one had seen him, even though he was the strongest and the only member of the Russian team to summit. This shows that he wasn’t someone who just wanted the limelight, but it was his sporting achievements and above all his human qualities that failed to pass unobserved.

Why do you say that he was first a man and second a mountaineer?

One could talk about this for ages. Just one example, at altitude everything’s an effort – walking, climbing, setting up camps and even more so to be unselfish. It’s so hard up there and you can’t afford to be yourself. Anatolij was the only person who prepared something to eat and then said “you eat first, then I’ll eat” or he pretended to not be hungry and gave me more to eat because he saw I needed it. He always looked after me and those around him before looking after himself.

From this one can understand the human qualities of someone who suffered like the rest of us, who earned $20 a month – he had all the right in the world to be everything but altruistic. This shows how in the storm of ‘96 he found the motivation to go back out and save the clients.

How did you meet him?

I was between Camp 1 and Camp 2 on Shisha Pangma. I was making the track and every now and then I sat down to rest and I saw him trying to reach me. When he did he hit my shoulder/patted my back and said, “thanks, you’re doing a great job”. Our friendship took off from there and in ‘97 we struck on the idea of the Lhotse-Everest traverse. We wanted to first climb Lhotse, descend to the South Col and then climb Everest from there. We retreated from the summit of Lhotse because conditions were appalling, so much so that on that that same day the incredibly strong Russian Vladimir Baskirov and four other Russian climbers lost their lives.

I would like to point out to those who said we quit because I wouldn’t have managed that the moment we decided to escape five people died and so conditions were quite obviously very difficult indeed. We retreated principally because the weather didn’t allow us to proceed. It’s clear that being on top of Lhotse wasn’t like a walk in the park and we were exhausted because we’d climbed without oxygen, but we still had enough energy to get to the South Col. We had a tent there which Anatolij had put up before. All the premises were there to at least fail during our ascent of Everest and not immediately upon reaching the summit of Lhotse. We didn’t do it, but we were the first to state that we wanted to do the traverse, the first to show our faces and try.

And then?

Then, when we were still at Lhotse Base Camp, came the decision to try Annapurna. This was obviously the most dramatic experience of my life because I lost two of my companions: Anatolij and the cameraman Dimitri Sobolev. Many people say that we asked for it, but in reality disaster struck on a face that was chosen because it avoided the dangers. We wanted to do the South Face in winter in alpine style. But when we arrived at BC it continued to snow and in the end it was more than four meters deep.

Avalanches kept coming down the South Face and we knew that we’d be risking too much by going up it, so we tried to reach the summit along the unclimbed East Face, which is harder but safer since it’s steeper. Our idea was to climb the face and follow the crest to Annapurna Fang, 7900m and then continue on to the summit. Nothing came down in the one and a half months that we were in BC. So we avoided the risky option and chose a harder but safer project.

But it was a decision that backfired because the first and only thing that came down was the avalanche that killed Anatolij and Dimitri, and narrowly missed killing me. I was dragged down 800m. I’ll recount it in a book – a book that doesn’t want to speculate about a tragedy, and whose profits go to these men who earn $12 a month.

What has struck you about the Himalayan sphere?

I’ve discovered that the Himalaya is a world without God, a world that’s too full of itself and better off not believing in God because its convinced it can go anywhere. I believe in God and am not ashamed to say it.

In this precise instant, what are you thinking of?

That I’m going to retry the project I had dreamt about with Anatolij Burkreev: the Everest – Lhotse traverse, the other way round though. This for two reasons, the first being extremely practical: it would be a shame to renounce on the summit of Lhotse, which I have climbed twice already, unlike Everest which I have never been up before. In doing this I would also throw away $15,000 for the permit, without even trying it.

The second reason, but perhaps the first in order of values, is that of the two Everest is harder to prepare for psychologically. Doing the harder section first may help me later. If I manage to get to the South Col after having summited on Everest I might be able find the will and desire, instead of descending to Base Camp, to return to Lhotse along the crest which, incidentally, has never been climbed before, even though the line is logical. I will try this crest because I already eyed it up in1997. During our ascent of Lhotse we left our rucksacks exactly there and I saw that one of the hardest sections is in fact more vulnerable than I thought. So much though will depend on the snow conditions.

But, I repeat, the real problem will be to summon up the energy, more mental than physical, to climb Lhotse after having been on Everest without oxygen. Up there one is at the cruising height of a Jumbo jet. It's like sitting on a wing, with the same wind and temperature, but the only difference being that you arrived there on foot and you have to find the will to wait and jump on another one which returns, on foot of course.

Will you climb alone?

I would have liked to be with someone, with Anatolij, but that clearly isn’t possible. Last year I met Denis Urubku and together we climbed the five 7000m peaks in Russia. Or rather, he climbed all five and I stopped after the fourth because I felt unwell. He’s someone who’s got the “umpf” and right drive for a project like this one, but he only earns $12 a month and I haven’t got the money to pay for his costs.

With a couple of tricks I managed to invent the possibility of me paying Lhotse for him, so I’ll have him as a companion for 50% of the route. He’ll wait for me on the South Col and then he’ll climb Lhotse with me. He’s also an excellent cameraman and this financial acrobacy was possible because we hope to sell his films of the traverse.

What is your programme?

To go to the South Col and first climb Everest, then Lhotse – to connect the two summits. All will depend on the conditions. It’s a bit like the wind when one goes sailing. If it blows, then one can sail, otherwise one can’t. In my case I’ll go if the conditions are right. If not, then I won’t.

How do you train?

I’ve trained both technically and physically. The technical training has consisted in being able to do 8a on rock, 6+/7- on ice and M8 on mixed routes. I think that having this technical level should give me the psychological edge at altitude.

The physical training has consisted in training as if for a marathon. This means that I’ve tried to improve my aerobic threshold, to teach my body to go as far as possible without producing lactic acid. Instead of going as far as possible in an hour I’ve tried to go as far as possible in an hour using only my aerobic mechanism, without producing lactic acid. This type of training has only been possible thanks to a medical team provided by one of my sponsors.

So you control you heart beat?

At a certain heart rate, in theory, it’s possible to go on forever without producing lactic acid, but if we want to go faster then we start producing it. This threshold can be raised through specific training, and so I’ve trained my body to go as fast as possible without producing lactic acid. If in the beginning I started producing lactic acid at 150bpm, I then moved that threshold to 160, to 162 and then to 168 bpm.

Where does this threshold lie at 8000m? And where do the famous ten paces and then a rest fit in to this?

Good question. All studies so far, even the most expensive and detailed, have been designed to find out what happens to the human body at altitude, but none have yet discovered the best strategy for altitude training. The heart is a muscle that, like all others, suffers when oxygen is lacking. When one first arrives at Base Camp the heart beats at about 90/100 times a minute. When I push myself as much as possible, like the time on Shisha Pangma, I discover that I never exceed 150/160 bpm, compared to 195/200 which I get when I train at sea level.

I tried to analyse this with the help of the medical team so that I could train and teach myself to use only my aerobic system and avoid producing the dangerous lactic acid, which you can’t get rid of at altitude. Since it’s like poison for the muscles it makes progress more dangerous. We’re in the process of trying to understand many things and we’re looking for firm answers also because recording my heart rate while climbing at altitude, which is very different from having the data of someone sitting in a tent at 7000 or 7500 meters.

And what about your nutrition?

I’m going to take food supplements because one of the biggest problems at altitude is that one doesn’t want to eat and, since weight is measured down to the last gram, one is always undernourished. One drinks very little, eats even less and has no appetite whatsoever. There are a whole series of limitations which stem from objective problems that result in people coming back having lost 6 or 7 kilos.

I’ve calculated that I’ll need 6 days for the traverse. Spending six days on the wing of that famous Jumbo, without anyone passing anything to eat through the window, isn’t much fun.

What is your strategy for 8000m peaks and the Everest – Lhotse traverse in particular?

To acclimatise so as to give my body the possibility of feeding off oxygen when higher up. For the traverse I want to arrive at the South Col, spend at least one night there and, before heading back down to Base Camp, climb up to 8100/8200m. Then I’ll descend into the valley, probably to Namche Bazar at 3700 m, or possibly even lower.

There I’ll eat well, I won’t be able to see the mountain which will already make me feel pretty sick, I’ll meet other people, see the forest, smell the smells and have a shower. The desire to see the mountain will return, and while all these things are happening my body will be adapting as much as possible, in a way that it couldn’t do at Base Camp.

And then go, back up to the Traverse. We’ll see if it’s a winning strategy.

Simone Moro

- born in 1967.

- Mountain Guide, athlete, Federal climbing Instructor and F.A.S.I. Italian sports climbing coach from 1992 to 1996.

- He has climbed full time for 19 years and has taken part in expeditions to some of the highest mountains in the world

(Himalaya, Andes, Patagonia).

- He has made numerous first ascents from the ground up, above all on the long alpine Presolana faces.

- He resides in Bergamo where he organises his expeditions, the Mountain Guides Association and PR campaigns

1992 Everest (unsuccessful)

1993 Aconcagua and Cerro Mirador (winter ascent); Makalu (unsuccessful)

1994 Shisha Pangma - 8008m; (unsuccessful); Lhotse (8516m) oxygenless ascent in 13 hours (17 total), from 6300 metri. The ascent stopped just short of the summit due to dangerous cornices.

1995 Kangchenjunga (unsuccessful)

1996 Fitz Roy (3441m) West Face via 'Supercanaleta', in alpine style and in atotal of 25 hours; Dhaulagiri (unsuccessful); Shisha Pangma Sud (8008m) oxygenless ascent in 20 hours (27 total) departing from Base Camp , descent with skis from 7100m.

1997 Lhotse (2nd personal ascent) without oxygen; Annapurna unsuccessful attempt at the first winter ascent. Cut short due to the deaths of Anatoli Boukreev and Dimitri Sobolev.

1998 Everest (unsuccessful)

1999 Pik Lenin (7134m), Pik Korjenevska (7105m), Pik Kommunism (7495m), Pik Khan Tengri (7010m). In 33 days overall.

Sponsor: Nike, Camp, The North Face , Polartec, Salice eyewear, La Sportiva, Longoni Sport, Tecno Project, Convertex. Gensan food supplements

Gear: Ski Trab, Salumi Bordoni.

Copia link

Copia link

See all photos

See all photos