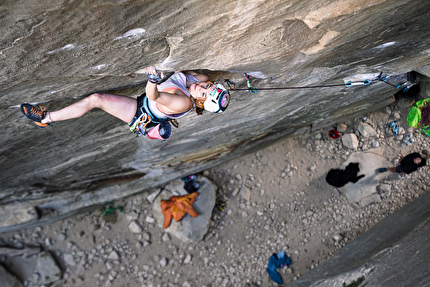

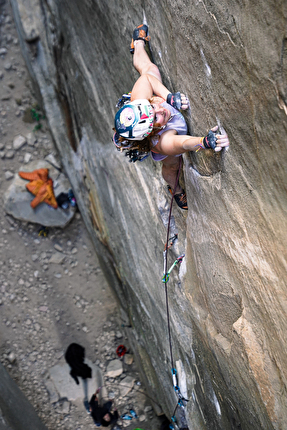

Soline Kentzel repeats Le Voyage at Annot

1 / 6

1 / 6 Julia Cassou

Julia Cassou

Setting a new personal best is always an extremely satisfying moment, especially if it comes after months of dedicated effort. In Soline Kentzel’s case, the satisfaction must be twice as big as a fortnight ago at Annot in France she repeated James Pearson's 2017 testpiece Le Voyage and upped her game twice. Not only is this the Frenchwoman’s first E10, with its 8b+ difficulties it also happens to be her hardest climbing grade in sport climbing as well. Here’s her fascinating story.

MY VOYAGE by Soline Kentzel

Le Voyage always had a mystical dimension in my eyes. I no longer know exactly how the desire, mixed with anxiety and curiosity, to confront it appeared, but it has been on my mind for a while. Was trying my maximum level in trad climbing the logical next step in my climbing journey? Is it pretentious? This is the feeling that comes over me, while watching a video of Babsi Zangerl, who happens to be the climber I admire most. In any case, as I often like to say: if everything goes wrong, it would still be excellent training for my future goals.

The first attempts confirmed my fears: dangling on the static rope, I understood nothing about the climb, and the gap between the protection seemed quite frightening. Nevertheless, it was love at first sight. Firstly because it's beautiful but above all, because I realised the magnitude of the challenge this line represented for me. I realised that I dreamt of being a climber capable of reaching the top of this wall; and that, physically and mentally, I was not there yet. Becoming that climber, capable of climbing the line of her dreams, that unique crack that escapes towards the sky, would henceforth be my reason for climbing.

Le Voyage follows an obvious line of weakness for 40 meters, which can be broken down into three parts. The route starts with a fairly technical 7a+ crack leading to a full rest. After this rest, a few moves lead to a good knee rest that allows you to breathe and prepare for the first crux. This first crux is quite long: a setup followed by some very fingery moves with terrible footholds to reach far into a pocket, all quite high above a good flake. After that, you need to quickly change pace to traverse on pockets, protect in this airy and rather committing section, and reach a decent rest where it's possible to place very good gear. Coming out of this rest, it's difficult to chalk up for the next 15 moves: you climb a bit before quickly placing the last piece of protection; for me, a #0.2 cam. The hardest (and quite pumpy) section begins here: a series of vertical handholds and thin edges for the feet that place you in some very uncomfortable positions. At the end of this section, you will have climbed about 2-3 meters above your last small piece of gear, and it's possible to clip an excellent flake. From here, the final section, which is about 7b, remains, the most committing part of the route: a run-out of at least 8 meters for some easy but nerve-racking climbing, and finally, the very technical final crack with tight hand jams.

So the work begins; in the beginning, I had to get back to climbing with cams in the surrounding routes, acquiring the ease needed to work the moves and also evolve on the static rope, hanging in the air. During the first trip, a pulley injury prevented me from focusing on the upper crux, which is on small holds. Instead, I focused my attention on the lower crux, which I painstakingly tamed. I was particularly bothered by the foot placements, which seemed either too low or too off-center. I could see that it was possible, but it would take a lot of attempts to piece together the puzzle and get used to the discomfort of these moves. I quickly jumped on lead. During the second trip, I still couldn’t link the entire lower crux; I repeatedly took long falls, often scaring my belayers more than myself. Gradually, my finger improved and I could seriously work the upper crux. It took me several hours to master all the moves intrinsically. All of them, except one, which I struggled with daily: the very last move of the hard section, to reach the final jug. On the last day of the trip, after a two-hour session hanging on my grigri in front of the section, I finally discovered MY beta. A layback move, pulling on the final holds, to move my feet just that little bit higher. On one hand, I expected this moment and knew it would come: the eureka of the route worker. On the other hand, I was disheartened: the sequence seemed extreme, demanding on the fingers, with the moves 30 meters off the ground, at the very end of a resistance section. In short, I was frustrated no miracle method, just pulling hard on the holds would do the trick.

On the third trip, the stakes changed. I arrived knowing that I was ready and here to give it some serious tries. Thus began the routine of "two tries a day keeps the doctor away." Since then, I almost exclusively led the route. When I couldn’t pass an obligatory section, I would ascend on the static rope to place the next pro, then continue leading. A key moment of the mental process was clearly passing the first crux. After this, the spiciest part of the route lay in store: already 3 big meters above the previous pro, small pieces had to be placed that didn’t inspire much confidence. Then you keep climbing a demanding and uncomfortable section, all the while trying not to get too tired. The first time my fingers got stuck in the far-away flat pocket at the end of crux 1, I found myself suspended in the moment. My brain started to fog and when my thoughts cleared, I realised that my heart was beating too fast. Controlling this emotion, acting on these thoughts to control my body, was an exciting challenge. Because there's no doubt that the more fear takes over, the higher the chances are of making a mistake and falling. On each attempt, this section would always prove an intense moment. I continued climbing to the next good piece of por each time, but with a clarity of mind and precision of movements that were quite random. At some point, the biggest mental challenge became accepting that each run is unique and that it’s impossible to predict and reassure myself that everything would be fine. This undoubtedly reflected in my climbing.

On the fourth trip, arriving more tired and less vigorous than before, I felt overwhelmed. By the apprehension and the weight of the pressure I had put on myself before returning, I began to have doubts. Whereas ten days earlier, I was falling in the middle of the upper crux, I was now repeatedly falling on the first crux. I armed myself with patience and continued to make attempts, some more promising than others. I had been camping on the floor of my friend Mich’s van for a week, who was also struggling with his project. We were both fixtures of the place, starting to become part of the scenery at Annot... I saw guys come, try the route, and leave (congratulations to Philippe, Jean-Eli, and Jabi who also climbed the route this season!), and I was still there. In the end, the rain showed up and we felt tired: it was time for Mich and me to leave, to regenerate our motivation.

I'd spent several weeks climbing and spending all my time exclusively with men. When my friend Juju joined me a few days, I realised how much I missed and felt sad about not having female friends to share my experiences with. In climbing, as a woman, the further you stray from the beaten path, the more alone you are. Yet, trad climbing shouldn’t be such a virile activity: everyone decides their level of commitment, and what a pity to miss out on the satisfying movements of crack climbing! For me, it’s not necessarily much more dangerous, it’s just climbing, but with even more freedom.

At the end of this fourth trip, a bitter feeling took over. While I was convinced that whatever happens, I would keep banging my head against this route and eventually succeed, my confidence took a hit: I realised that my body might not be as strong as I wanted it to be. In particular, I wondered if I could ever, soon, measure up to the climbs that make me dream without my chances being largely based on hard work, patience, repetition, and optimism.

When I came back the fifth time, my mindset had evolved. I arrived more humble, more prepared for things not to go as planned, and found ways to reduce the pressure. Some of my close friends were there, and I felt their support. Deep down, I knew this time I was here to deliver the final blow and that I wouldn’t leave without succeeding, no matter the consequences for my studies and other obligations. Finally, this time, the stars aligned. Or almost. On the second day, I fell with my hand in the final jug, a bit too low, probably due to a left biceps failure. No problem, I had automated the sensations, and it was now only a matter of time.

When I finally linked the moves, encouraged by my friends, not a grain of sand disturbed the unique sequence of this vertical precariousness. Even the run-out section after the upper crux didn’t upset my serenity (though my legs trembled a bit — it had been a while since I'd left the ground…). I breathed calmly before engaging in the very last section, a round and awkward crack that had caused more than one drop of sweat. And then I clipped the anchor, overwhelmed with immense relief: I could finally end this exclusive relationship and leave this jewel behind. Enjoy a few moments of respite, before falling once again into the trap of another dream line.

Copia link

Copia link

See all photos

See all photos