Lest we forget: the Italian racial laws, the Italian Mountaineering club and its Jewish members

1 / 33

1 / 33 CAI

CAI

On January 27, 1945, Red Army soldiers gathered outside the gates of the Auschwitz concentration camp. Before them lay the darkest period in human history, an insanity that, in a handful of years, forever marked an era. An atrocity that somehow crossed over into all domains, including the mountains. Or rather, attempted to contaminate the high lands, but actually managed to do little more than scratch the bureaucratic soul of its slopes. The heart of mountains, back then far more than nowadays, was a place for sharing, for helping, for unity. These were the lands of partisans, hidden away in the forests, ready to fight for an ideal of freedom and justice.

"All the central and peripheral CAI directors (even commission members) must be exclusively of pure Aryan race". These were the words that opened the "highly confidential" internal document sent to all climbing club sections by the National council, on December 5, 1938 only a few months after the Italian Council of Ministers had approved the "laws for the defence of race". The internal note went on to indicate the criteria set out to the purge members of "non-Aryan race", then specified that "these provisions are strictly confidential and must not, under any circumstances, be communicated to the press or, in writing, to the interested parties".

This letter heralded one of the last steps in the fascistization of the Club Alpino Italiano, a process that had begun in 1927 with the annexation of the club to CONI, the Italian National Olympic Committee, that quickly led to the total loss of democracy within the club. CAI directors were now appointed via a Decree of the Head of Government, following the proposal of the Secretary of the fascist party. These were then entrusted with appointing section presidents. The one prerogative, shared by all, was fascist party membership.

Shortly afterwards, the CAI headquarters were moved from their birthplace city Turin down to Rome, in order to experience "the life-giving breath of fascism", as the then general president Alfonso Turati explained. Changes soon followed regarding the running out the mountain huts, as wardens and staff now had to be selected and vetted by the party in order to eliminate potential anti-fascists. Furthermore, forty thousand youngsters from the Fascist University Groups joined the ranks of the CAI, so as to lower its average age, while a military president was appointed and the club’s name transformed into something sounding more Italian. As of 17 May 1938, the Italian Alpine Club would no longer be called the Club Alpino Italiano, but Centro Alpinistico Italiano, Italian Alpine Center.

The final act was the application of racial laws, which mmediately resulted in the systematic exclusion of both ordinary club members and members for life. For the former, the document stated "if they have paid the current annual fee [...] it may be reimbursed". Radical measures soon followed, as for example by the Società Alpina delle Giulie which practically anticipated the document and almost immediately got rid of all its Jewish members. Other sections clearly indicated the new rule to all those wishing to become members: are you a Jew? Well you will not be accepted and your membership will not be renewed.

This happened for example to Turin-based mathematician Emilio Artom who, even before being excluded from his local club, had to deal with the consequences of not joining the Fascist party. Worse happened to the composer Leone Sinigaglia who was, as is written on a Stolperstein dedicated to him, "persecuted by the Italian racial laws of 1938. Died on arrest". On May 15, 1944, a Monday like all others. The same fate befell hundreds of other members, purged from club membership while everyone looked on with indifference and embarrassment. No one tried to protest, to shout out in favour of their friends, their climbing partners with whom they had spent nights up in the mountains, with whom they had shared meals at campfires. Perhaps Primo Levi was indeed right when he said that "the CAI guidebooks were only of use when one did the exact opposite of what they recommended.”

Get rid of the living and also the dead. The Italian Alpine Center showed no mercy, not even for its past. Without delay, according to the note from the National Council, the local sections were told to rename those huts named after Jewish mountaineers. Hence Rifugio Marianna Levi was replaced in favour of Magda Molinari; Achille Forti, at the foot of Monte Tomba, became Rifugio Giovinezza. Visitors to the Dolomites will certainly know Rifugio Coldai; before the racial laws came into effect, this beautiful hut was named after Adolfo Sonino, the Venetian mountaineer who had fallen to his death on Punta Fiames in 1930.

These vicissitude concerning the CAI remained dormant for years. Almost fell into oblivion, as the desire to leave the war behind and forget about those dark years got the upper hand. They resurfaced however eighty years later, when Italian journalist and historian Lorenzo Grassi published his research entitled: "The purge of the Jewish members of the Urbe section of the Italian Alpine Center".

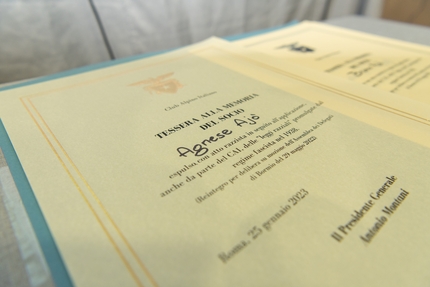

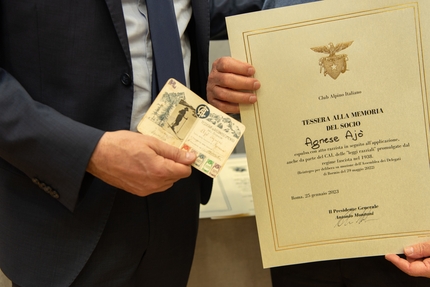

The reaction to his report was immediate and far-reaching: in May 2020 at its National Assembly the CAI delegates unanimously voted in favour of further analysis, self-examination and assumption of responsibility. And this, on 25 January 2023, resulted in the formal readmission of all members purged from CAI’s Rome section. Heirs were issued with membership cards in memory of their ancestors.

Wednesday’s celebration in Rome was an important step in the right direction, and other initiatives will follow in due course. In order to remember the past and recount the truth. For this is our perpetual obligation.

by Gian Luca Gasca

Copia link

Copia link

See all photos

See all photos