Bjørn-Eivind Årtun and Venas Azules on Torre Egger in Patagonia. The interview and meeting with Rolando Garibotti

Rolando Garibotti and the interview and meeting with Bjørn-Eivind Årtun, the Norwegian alpinist who in December 2011 together with Ole Lied established the route Venas Azules up the South Face of Torre Egger in Patagonia.

1 / 6

1 / 6

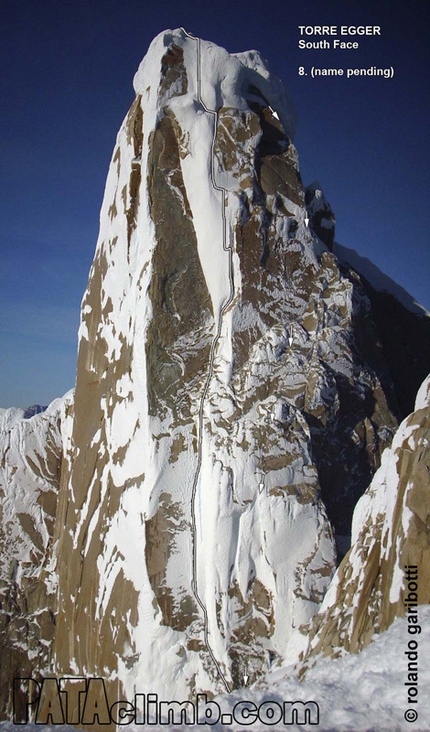

Venas Azules, Torre Egger, Patagonia.

archivio Bjørn-Eivind Årtun

archivio Bjørn-Eivind Årtun

Norwegian climber Bjørn-Eivind Årtun recently jumped into the news when he and Ole Lied climbed "Venas Azules", a fantastic new route in the south face of Torre Egger, an improbable ice line that many had looked at but that nobody dared to try. Bjørn -Eivind is a 45-year-old photographer and climber that lives in Oslo with his 12 year old daughter Iben. He is by no means a new name to Patagonia, having visited the area in five different occasions.

The presence of Norwegian climbers in Patagonia is a fairly recent development. After visits in the 1980's by climbers such as Aslak Aastrop and Øivind Vadla there was a long hiatus until Trim Atle Saeland started coming regularly, sometime in the late 1990's. Trim’s visits led to more and more Norwegian climbers coming to Patagonia and for the last few years they have become part of the "local fauna" and have been responsible for many impressive ascents. These include Trim and Ole’s first ascent of the much discussed Corkscrew route on Cerro Torre, and Bjørn -Eivind and Marius Olsen’s "Hvit Linje", an impressive waterfall under the serac just east of Aguja Poincenot.

Although Bjørn -Eivind started climbing in 1987 he only started alpine climbing about six years ago. For close to two decades he climbed mostly on rock, climbing the Troll wall for the first time in 1991 and collecting a good number of impressive repeats and first free ascents of trad routes across Norway.

He visited Patagonia for the first time in 2007 and has since done a number of important ascents, including a repeat of Los Tiempos Perdidos on the south face to Cerro Torre with Joakim Eide, repeats of Supercanaleta on Fitz Roy, Red Pillar on Mermoz, Exocet on Standhardt and an impressive 13-hour ascent of the Ragni route on the west face of Cerro Torre, from Niponino to the summit via the Standhardt col.

Let’s start by "Venas Azules" the route you just climbed in Torre Egger. It was talked about for a number of years, at least since 2005 when Ermanno Salvaterra first brought it up. When did you first see it?

I saw it in 2008 when I climbed the Ragni route. That year was exceptionally dry so I was able to see that under the rime there was blue ice, a series of ice veins that seemed to connect all the way to the top. As soon as I saw that I knew it was climbable. I considered climbing the left side of the upper mushroom but then realised that on the right side there was a thin half pipe. In 2010 I came to Patagonia with Robert Caspersen in hopes of trying it directly from the west side, via an obvious dihedral leading to the Egger-Torre col, to the "col de la Verdad" (Col of Conquest, Editor's note), hoping to climb a completely independent route, but unfortunately we never got the weather window we needed.

Trying such an uncertain line was the result of pure enthusiasm. During the climb we came to several spots where the veins of ice stopped and yet every time with a "blind" traverse we could find another vein that kept going, more ephemeral steep ice plastered on vertical rock. It was not until past the fifth pitch that we knew the route would go, once I climbed out onto the overhanging belly of the mushroom and could see another ice vein that connected to easier ground above. The fifth pitch was very pumpy, climbing the overhanging belly of a mushroom while having to clean off the rime that covered it.

When did you first come to Patagonia?

In 2007, I was nursing an injured elbow and thought that going alpine climbing was a good alternative. Pretty fast I felt at home. It felt so amazing to climb in the wind, in such amazing nature, a nature that in combination with the climbing made the picture complete so to speak. I was immediately hooked.

Since I first met you in 2007 it was obvious to me that you were motivated and inspired by ephemeral ice lines, from your ascent of "Hvit Linje", the impressive waterfall under the serac just east of Aguja Poincenot, to Los Tiempos Perdidos. I guess maybe it is inevitable that being Norwegian you would be attracted mostly to ice?

Although I can see how you would get that impression I consider myself a trad climber and an alpinist rather than an ice climber. I am not very inspired by pure waterfalls but rather I am inspired by ice climbing in big features, big-walls and alpine settings, by routes like the two I put up in Kjerag, a 900 meter wall right out of a Norwegian fjord that has several long veins of ice that cover it. The wind splashes water into a series of ice streaks, making the climbing very tenuous and tricky. It is pretty amazing climbing which requires both ice climbing and trad climbing skills.

As the ascent of these two routes in Kjerag proves, it is obvious that you have a strong aversion to the use of bolts in alpine settings.

In alpine climbing, an activity that has little to do with the physical, gymnastic aspect of climbing and much more with the psychological quality of the experience it seems pointless and limiting to take short-cuts such as drilling.

The times when getting to the top by whatever means was OK, are over. In an ever-shrinking world not using bolts is the progressive, more futuristic and "modern" thing to do. There is no hurry to develop the remaining virgin terrain, one needs to learn to wait for the right conditions or wait until one is up to the task. It is important to have projects out of one’s reach because they open the possibility for improvement, for dreaming. By using bolts in the alpine one limits one’s own development as well as the general development of the sport. Drilling is reductive.

We climbed the routes on Kjerag around the same time that Robert Jasper and Roger Schaeli came to Norway to climb some new waterfalls in our mountain valleys. They used a powerdrill and many bolts and many of us were flat out upset. A number of local climbers had been waiting for the right conditions to do one of those routes in a clean style. This led to strong reaction against the use of bolts in alpine settings in Norway that included a formal complaint by the Norwegian Alpine Club in the hope of making a clear statement that local ethics have to be respected. Sure, there is a place for bolts in climbing, but in an alpine environment they should be avoided as much as possible. One of the routes they climbed is called "Into the Wild", a perplexing name considering it was climbed using a powerdrill.

Also, more generally and philosophically, there is a certain beauty to untouched terrain and it is very important to not leave any trace of passage. Our actions should reflect respect for the greatness of nature. Leaving bolts, fixed ropes, "wall garbage" behind is not ok.

You were nominated to the 2011 Piolet d’Or for "Dracula", your new route in Mount Foraker, Alaska with Colin Haley. After being at that event, what are your thoughts about it?

I was not sure it would be worth participating in the Piolet d’Or, but I did sense that the intentions were good, so I went. It is a great event but I think it would be important to get rid of the concept of "winners" and to focus more on the inspiration that certain climbs can have, on the fact that giving attention to certain climbs can move the development of the sport in a certain direction. It can potentially be a very inspiring event, with good values. Meeting all the other climbers present was very inspirational for me.

Tell me more about Dracula. I know it was an old idea from Steve House and a few other climbers. Had you been to Alaska before?

Yes, I had been there the year before when we climbed the French route and the Moonflower buttress, both on Mount Hunter. Without that prior experience Dracula would not have been possible.

For me it was an important climb for the challenge that was going for it in uncertain weather, in a very short weather window. I believe that after a while you develop a sixth sense for what you can manage and in spite of the bad forecast I thought we should have a go at it. The allure and the motivation were strong.

My approach to planning climbs has a lot more to do with that sixth sense than with analyzing the details of a climb. That "sense" starts with a motivating idea that might be a bit far out, a bit of a dream, the kind of idea that when you think about it you say to yourself: "it would be cool but is it possible?"

Some people think first of the practical and logistical issues surrounding a climb, things like "do I have the skills required", how many days will it take", etc, for me it is the opposite, the process starts when I get inspired by a certain line, by a lofty idea, then I shape my imagination and dreams down to the realm of possibility. My approach is not practical, but it has paid off with a number of great adventurous climbs.

We need to allow ourselves room to be more daring. Too often by over-analysing and over-intellectualising climbs we confuse fear for real danger. It is important to learn to distinguish one from the other. There is a big difference between getting intimidated by the steepness, difficulty or length of a climb, and real dangers such as avalanches, rock-fall, limited options of retreat, cold, etc. Venas Azules is a good example, an intimidating line that is reasonably safe, with little objective danger. Being brave and open minded without compromising your safety is the fine line we walk in our hunger for adventure.

A big "in boca di lupo" for the next good weather window. I will be looking forward to being surprised yet again by another of your fantastic climbs.

Bjørn-Eivind Årtun is supported by Norrøna, Petzl, Beal and Scarpa

The presence of Norwegian climbers in Patagonia is a fairly recent development. After visits in the 1980's by climbers such as Aslak Aastrop and Øivind Vadla there was a long hiatus until Trim Atle Saeland started coming regularly, sometime in the late 1990's. Trim’s visits led to more and more Norwegian climbers coming to Patagonia and for the last few years they have become part of the "local fauna" and have been responsible for many impressive ascents. These include Trim and Ole’s first ascent of the much discussed Corkscrew route on Cerro Torre, and Bjørn -Eivind and Marius Olsen’s "Hvit Linje", an impressive waterfall under the serac just east of Aguja Poincenot.

Although Bjørn -Eivind started climbing in 1987 he only started alpine climbing about six years ago. For close to two decades he climbed mostly on rock, climbing the Troll wall for the first time in 1991 and collecting a good number of impressive repeats and first free ascents of trad routes across Norway.

He visited Patagonia for the first time in 2007 and has since done a number of important ascents, including a repeat of Los Tiempos Perdidos on the south face to Cerro Torre with Joakim Eide, repeats of Supercanaleta on Fitz Roy, Red Pillar on Mermoz, Exocet on Standhardt and an impressive 13-hour ascent of the Ragni route on the west face of Cerro Torre, from Niponino to the summit via the Standhardt col.

Let’s start by "Venas Azules" the route you just climbed in Torre Egger. It was talked about for a number of years, at least since 2005 when Ermanno Salvaterra first brought it up. When did you first see it?

I saw it in 2008 when I climbed the Ragni route. That year was exceptionally dry so I was able to see that under the rime there was blue ice, a series of ice veins that seemed to connect all the way to the top. As soon as I saw that I knew it was climbable. I considered climbing the left side of the upper mushroom but then realised that on the right side there was a thin half pipe. In 2010 I came to Patagonia with Robert Caspersen in hopes of trying it directly from the west side, via an obvious dihedral leading to the Egger-Torre col, to the "col de la Verdad" (Col of Conquest, Editor's note), hoping to climb a completely independent route, but unfortunately we never got the weather window we needed.

Trying such an uncertain line was the result of pure enthusiasm. During the climb we came to several spots where the veins of ice stopped and yet every time with a "blind" traverse we could find another vein that kept going, more ephemeral steep ice plastered on vertical rock. It was not until past the fifth pitch that we knew the route would go, once I climbed out onto the overhanging belly of the mushroom and could see another ice vein that connected to easier ground above. The fifth pitch was very pumpy, climbing the overhanging belly of a mushroom while having to clean off the rime that covered it.

When did you first come to Patagonia?

In 2007, I was nursing an injured elbow and thought that going alpine climbing was a good alternative. Pretty fast I felt at home. It felt so amazing to climb in the wind, in such amazing nature, a nature that in combination with the climbing made the picture complete so to speak. I was immediately hooked.

Since I first met you in 2007 it was obvious to me that you were motivated and inspired by ephemeral ice lines, from your ascent of "Hvit Linje", the impressive waterfall under the serac just east of Aguja Poincenot, to Los Tiempos Perdidos. I guess maybe it is inevitable that being Norwegian you would be attracted mostly to ice?

Although I can see how you would get that impression I consider myself a trad climber and an alpinist rather than an ice climber. I am not very inspired by pure waterfalls but rather I am inspired by ice climbing in big features, big-walls and alpine settings, by routes like the two I put up in Kjerag, a 900 meter wall right out of a Norwegian fjord that has several long veins of ice that cover it. The wind splashes water into a series of ice streaks, making the climbing very tenuous and tricky. It is pretty amazing climbing which requires both ice climbing and trad climbing skills.

As the ascent of these two routes in Kjerag proves, it is obvious that you have a strong aversion to the use of bolts in alpine settings.

In alpine climbing, an activity that has little to do with the physical, gymnastic aspect of climbing and much more with the psychological quality of the experience it seems pointless and limiting to take short-cuts such as drilling.

The times when getting to the top by whatever means was OK, are over. In an ever-shrinking world not using bolts is the progressive, more futuristic and "modern" thing to do. There is no hurry to develop the remaining virgin terrain, one needs to learn to wait for the right conditions or wait until one is up to the task. It is important to have projects out of one’s reach because they open the possibility for improvement, for dreaming. By using bolts in the alpine one limits one’s own development as well as the general development of the sport. Drilling is reductive.

We climbed the routes on Kjerag around the same time that Robert Jasper and Roger Schaeli came to Norway to climb some new waterfalls in our mountain valleys. They used a powerdrill and many bolts and many of us were flat out upset. A number of local climbers had been waiting for the right conditions to do one of those routes in a clean style. This led to strong reaction against the use of bolts in alpine settings in Norway that included a formal complaint by the Norwegian Alpine Club in the hope of making a clear statement that local ethics have to be respected. Sure, there is a place for bolts in climbing, but in an alpine environment they should be avoided as much as possible. One of the routes they climbed is called "Into the Wild", a perplexing name considering it was climbed using a powerdrill.

Also, more generally and philosophically, there is a certain beauty to untouched terrain and it is very important to not leave any trace of passage. Our actions should reflect respect for the greatness of nature. Leaving bolts, fixed ropes, "wall garbage" behind is not ok.

You were nominated to the 2011 Piolet d’Or for "Dracula", your new route in Mount Foraker, Alaska with Colin Haley. After being at that event, what are your thoughts about it?

I was not sure it would be worth participating in the Piolet d’Or, but I did sense that the intentions were good, so I went. It is a great event but I think it would be important to get rid of the concept of "winners" and to focus more on the inspiration that certain climbs can have, on the fact that giving attention to certain climbs can move the development of the sport in a certain direction. It can potentially be a very inspiring event, with good values. Meeting all the other climbers present was very inspirational for me.

Tell me more about Dracula. I know it was an old idea from Steve House and a few other climbers. Had you been to Alaska before?

Yes, I had been there the year before when we climbed the French route and the Moonflower buttress, both on Mount Hunter. Without that prior experience Dracula would not have been possible.

For me it was an important climb for the challenge that was going for it in uncertain weather, in a very short weather window. I believe that after a while you develop a sixth sense for what you can manage and in spite of the bad forecast I thought we should have a go at it. The allure and the motivation were strong.

My approach to planning climbs has a lot more to do with that sixth sense than with analyzing the details of a climb. That "sense" starts with a motivating idea that might be a bit far out, a bit of a dream, the kind of idea that when you think about it you say to yourself: "it would be cool but is it possible?"

Some people think first of the practical and logistical issues surrounding a climb, things like "do I have the skills required", how many days will it take", etc, for me it is the opposite, the process starts when I get inspired by a certain line, by a lofty idea, then I shape my imagination and dreams down to the realm of possibility. My approach is not practical, but it has paid off with a number of great adventurous climbs.

We need to allow ourselves room to be more daring. Too often by over-analysing and over-intellectualising climbs we confuse fear for real danger. It is important to learn to distinguish one from the other. There is a big difference between getting intimidated by the steepness, difficulty or length of a climb, and real dangers such as avalanches, rock-fall, limited options of retreat, cold, etc. Venas Azules is a good example, an intimidating line that is reasonably safe, with little objective danger. Being brave and open minded without compromising your safety is the fine line we walk in our hunger for adventure.

A big "in boca di lupo" for the next good weather window. I will be looking forward to being surprised yet again by another of your fantastic climbs.

Bjørn-Eivind Årtun is supported by Norrøna, Petzl, Beal and Scarpa

Note:

Latest news

Expo / News

Expo / Products

The ultimate shell pants for any winter outing.

Climbing Technology Climbing Technology Altimate - harness for ski touring and technical mountaineering

Innovative double configuration modular harness designed for ski touring and technical mountaineering.

Lightweight helmet for climbing, mountaineering and ski mountaineering.

Ocun Diamond S climbing shoes designed for maximum performance, comfort, and precision

Merino Wool Ski Mountaineering Sock.

Hardshell jacket for technical mountaineering and climbing.

Copia link

Copia link

See all photos

See all photos