Lynn Hill and Katie Brown's free ascent of Leaning Tower

Last July Lynn Hill and Katie Brown made a free ascent of Leaning Tower's West Face (Yosemite, U.S.A.).

| Last July Lynn Hill and Katie Brown made a free ascent of Leaning Tower's West Face (Yosemite, U.S.A.). The two American climbers carried out the ascent in various stages, demonstrating once again that top ascents and female climbing can easily go hand in hand. Unsurprisingly some might say, since Lynn Hill is without a shadow of doubt one of the climbers who has most left her mark on the vertical world in these last twenty years (on all counts, both in competitions and outdoors). And as many will remember, Katie Brown is the young shooting star of '90s who upstaged all vertical parameters (remember those two consecutive Rock Master victories?). While we lost trace of Katie as she began her studies at College, Lynn published her book entitled "Climbing Free. My life in the vertical world" and began her adventure with her son Owen, the beautiful baby boy with her same blue eyes... This is why Lynn's story of their Leaning Tower ascent, and the re-introduction of Katie Brown, seems interesting to us. What a journey! And, above all, what a demonstration that climbing is deep rooted, that it entices back and unites people, regardless of their personal experience and age.. LYNN HILL AND KATIE BROWN'S JOURNEY Yosemite Valley: West Face Leaning Tower by Lynn Hill  Raising a very curious and energetic two-year old involves a roller coaster of emotions; joy, frustration, fear, laughter, love, sorrow, and many other feelings that I didn’t even know existed prior to having Owen. I knew it would be trying at times, but so far the good times make all the effort worthwhile. I enjoy challenges that require trying to do my best. Perhaps this is why I’m inspired to keep climbing after all these years. I can always do it better… Raising a very curious and energetic two-year old involves a roller coaster of emotions; joy, frustration, fear, laughter, love, sorrow, and many other feelings that I didn’t even know existed prior to having Owen. I knew it would be trying at times, but so far the good times make all the effort worthwhile. I enjoy challenges that require trying to do my best. Perhaps this is why I’m inspired to keep climbing after all these years. I can always do it better…After a brief phone conversation with Katie Brown, I decided to fit one more thing into my already busy schedule: to try free climbing the West Face route on the Leaning Tower with her. The first two pitches of the route follow up an overhanging bolt ladder, but the rest of the route goes free at around 5.13. Katie had been up the first four pitches the summer before with Adam Stack and was looking for someone to climb the rest of the route with. I was just the person to call. I met Katie when she was a teenager living in the South East and traveling around with her mother, who belayed her and accompanied her to various climbing areas and competitions. Judging by her svelte appearance, Katie couldn’t have weighed more than 80 pounds. Though she wore a face of nearly constant neutrality while climbing, on occasion she would surprise everyone by making a sudden jump or power-glide upwards on impossibly difficult terrain, and only then would her face show momentary signs of vulnerability. She appeared invincible. After watching Katie win nearly every competition she entered, I realized she was one of the most talented climbers I had ever seen. She seemed to have a keen sense about exactly where to place her feet and hands without hesitating or wasting energy. It seemed that no matter what Katie was always able to figure out a plan of action and execute it to perfection. Over the past five years I kept in touch with Katie but rarely saw her between her studies in College and occasional trips to Colorado to visit family and friends. The first time I saw her after she had moved back to Colorado, I was surprised to see how beautiful she looked as a mature woman. She had grown up. Katie had taken a break from climbing during her years at College and I was happy to hear that she had recently gotten back into climbing and was frequenting areas like Moab, Yosemite, and many other climbing destinations at home and abroad. Since Katie started climbing on sport crags during the mid 90’s, she didn’t have the opportunity to learn much about traditional climbing. Although many aspects of climbing have changed since I was her age, the fundamental elements remain the same. And no matter how many times I’ve climbed in Yosemite Valley, it’s still one of the most humbling, daunting, physically demanding, yet spectacular places I’ve ever been. Getting to the base of the Leaning Tower involved a one-hour hike up hill through large boulders, a thick Pine forest with voracious mosquitos, along the base of the wall and finally, across a third class ledge system leading out to the middle of a massively overhanging wall. After ascending a fixed line up this wall for 250 feet, we arrived at a small ledge demarcating the beginning of the free route. Fortunately the weather was unusually cool and we were able to check out the first four pitches while it was still in the shade. Of course, I always try to climb as well as possible, and ideally, to climb everything on-sight. But since I had been busy with many other projects and not climbing consistently, I didn’t expect to do it completely on-sight. Our goal was to climb every pitch free, alternating leads all the way to the top. Katie chose to lead the first pitch up a steep dihedral with wide stems and the occasional thin finger jam, or face hold. Though it wasn’t an ideal warm-up at 5.12c, but we both climbed it. The next pitch was the so-called crux, which followed up a steep face with a shallow corner system leading out of sight from the belay. I made it through the first bit of strenuous climbing to the top of the corner system until I could no longer see where to go. Once I rested, I found a hold underneath some vegetation in a shallow seam and climbed up to the tricky slab at the end of the pitch. After trying a few different methods, I found a crucial knee bar using my knee against a hand hold and my foot smeared on the sloping face beneath a small roof. This allowed me to stabilize my weight enough to reach up to the key hold on the slab below the anchors. I figured the climbing would be easier above but this didn’t turn out to be the case. Off Guano Ledge, the free variation involves making a long reach sideways to a large ledge that leads across a 5.12b ramp system. Katie went up and tried to find a way past this section and ended up taking tension to get past the move. She continued climbing up another two-thirds of the way before relinquishing the rope to me.  When I arrived at the first crux, I quickly decided that the way taller climbers had spanned across to the ledge would be too far for me. Instead I chose to follow the original aid line up a thin crack until I could reach out to a crescent shaped feature on the face to the right. In order to join the ledge system further right I needed to make a dynamic heel hook, then another couple of desperate slap moves to finally get over to the big ledge. Once we figured out exact how to do this move, we continued onto the next pitch, which had a reputation for being a scary lead. Once I began climbing this pitch, I discovered why: there was a double garage door sized flake of granite precariously attached to the wall in the middle of the pitch! Fortunately it was easy enough to climb around it and avoid placing protection behind it, but the closest place to get any protection in the rock was another forty feet above in thin, grass filled crack! Though the crux move on this section was fairly well protected by the bolt ladder, the moves were very insecure. In fact, as I was pulling on a hold that I could barely reach at full arms stretch, I mentioned to Katie that I could hear granite crystals grinding under my hand. When she arrived at this spot, I watched Katie and the key hold suddenly fly off backwards. Our plan was to rest the following two days, then give the route a try from the ground. We had no idea whether or not there would be an alternative way to get past the crux move. When I arrived at the first crux, I quickly decided that the way taller climbers had spanned across to the ledge would be too far for me. Instead I chose to follow the original aid line up a thin crack until I could reach out to a crescent shaped feature on the face to the right. In order to join the ledge system further right I needed to make a dynamic heel hook, then another couple of desperate slap moves to finally get over to the big ledge. Once we figured out exact how to do this move, we continued onto the next pitch, which had a reputation for being a scary lead. Once I began climbing this pitch, I discovered why: there was a double garage door sized flake of granite precariously attached to the wall in the middle of the pitch! Fortunately it was easy enough to climb around it and avoid placing protection behind it, but the closest place to get any protection in the rock was another forty feet above in thin, grass filled crack! Though the crux move on this section was fairly well protected by the bolt ladder, the moves were very insecure. In fact, as I was pulling on a hold that I could barely reach at full arms stretch, I mentioned to Katie that I could hear granite crystals grinding under my hand. When she arrived at this spot, I watched Katie and the key hold suddenly fly off backwards. Our plan was to rest the following two days, then give the route a try from the ground. We had no idea whether or not there would be an alternative way to get past the crux move.After two days of rest, we found ourselves back on this dramatically overhanging wall, ready to give it a try. Katie cruised up the first pitch and I felt clumsy while following, trying to both warm up and conserve my energy at the same time. I was psyched to give the next pitch my best effort since this was the hardest pitch on the route. Despite getting a flash pump on the lower section, I managed to pull through without falling. Katie was able to follow the pitch flawlessly and we felt confident about our chances to free climb every pitch to the top. Little did we know what challenges awaited us above. The next pitch off of Guano Ledge was Katie’s lead and she wasn’t sure she could do it on the first try. It ended up taking three tries before she was able to stick the dynamic heel hook move and slap her way across this desperate section. Next it was my turn to lead the scary pitch where the key hand hold had broken off. The crux move involved going from a large foot hold on the face, to a small ledge above. The main problem was the large distance between these features with virtually no holds. To keep myself from falling out backwards, I used two shallow depressions in opposition between hands, then I smeared my left foot on the face, then sprang upwards high enough to slap my hand onto the sloping ledge. Once I made it past this crucial move, I felt confident about the scary climbing above. My climbing style is slow but sure, in keeping with the first rule I ever learned as a climber: “don’t fall”. In times like this, I can’t help think about Owen. I heard that familiar voice of conscious reminding me not to take unreasonable risks. Little did I know that at that moment Owen was suspended on a slack line stretched above the Merced River with Dean Potter (who shares the same birthday as Owen: April 14th). At one point, Dean actually let go of Owen’s hand and for a split second, allowing him to stand there by himself! Of course, I trust that Dean was capable of handling the situation safely (as well as the several climbing friends standing by to help if necessary), but I bet any other mother’s heart would leap out of their chest if they saw their child in such a situation. Luckily I made it past the insecure face moves just before the sun came around to bake the handholds. Katie didn’t have this advantage and she ended up falling a few times on this move. Typical of Yosemite granite, getting past this steep and smooth face involved a complicated coordination of push/pull forces, which I was used to encountering on granite. In the old days, there were many face climbs with similarly delicate moves and it was a rite of passage to be humbled on these so-called classic routes. But Katie is a quick learner and after a few tries, she was able to do the move exactly how I had done it. It was fun to be able to share beta and compare approaches with someone who was exactly the same height as me! The next pitch followed up a long and strenuous crack system for 140 feet! The first few moves involved scarcely protected climbing on a thin and polished crack. I shouted a few words of encouragement as Katie tenaciously worked her way up the pitch. I was impressed with her lead as I followed this unrelenting pitch. The next few pitches above would not be easy either. We had forgotten to bring the topo so I wasn’t sure if I should continue climbing when I reached a belay only forty feet above. Katie encouraged me to keep climbing since we were both curious to check out the intimidating roof that loomed above. The afternoon sun was beating down in the corner leading up to the roof and my feet were throbbing with pain. I climb up and down this section a few times trying to reach to a hidden hold above. I kept reaching up at full arm’s stretch to a place that was covered in duck tape, an aid climbing strategy for protecting the rope against sharp edges. After a few efforts, I was able to rip the tape off and I eventually found a key edge to get past this section. By the time I finally went for it, my pain tolerance was spent and I fell. After resting at the belay and taking off my shoes for a few minutes, I went up again and this time I fell off again while trying to pull into the roof. At that point I told Katie this would be my last attempt before turning over the lead. I was at that critical point of fatigue when performance starts to decline. I had been in a similar situations before throughout the years, and I knew that this time I would need to put forth my maximum effort . I climbed through the first crux and into the roof to some thin hand jams. Though my hands were secure, it was extremely difficult to place my feet on the rock. I ended up using a combination of techniques like throwing my leg into a pod, different sized hand and fist jams, dirty face holds, until I finally arrived at the edge of the lip desperately pumped. Rather than give in to my sense of fatigue, I quickly threw my hand into a hand jam and I finished the pitch. I knew this would be a tough pitch for Katie to follow. She made it up the first part with elegant ease, but fell at the lip of the roof. Since I was so far above, I could barely hear her when she explained that she was hanging in space and couldn’t get back onto the rock. I yelled down to her that she should “wrap a sling around the rope” and fortunately she understood. A few minutes later she was back on the rock, but physically and mentally spent. When she arrived at the belay, there was pain written all over her face: pain from the hard struggle she had endured and pain from her sense of frustration. I had been there many times before and I understood why she was disappointed to have “fallen” short of her usual level of perfection. But sometimes things don’t turn out like we hope. And in Yosemite, I found that the more rules you impose on yourself, the more you get out of the experience. I reminded her that she had done a great job, and that once she had rested, I could lower her back down to try the pitch again. There was one more pitch to the top of the route and it looked like yet another strenuous crack system requiring a heavy rack of gear. As it turned out, this last pitch was a dramatic way to end our adventure. We encountered a strenuous corner where I felt too tired to stop and clip the fixed pro, fist jams around an awkward bulge, flaring hand jams in a guano (bat-shit) filled crack, and a bit of crumbly rock. By the time we both reached the last belay, it was dark and it was time to go down. Despite the falls, I was happy to have free climbed the entire route but I felt bad that Katie didn’t have the same sense of satisfaction. At that point, we agreed to go back up on the route once we got back from a quick trip to Squamish for the Petzl Roctrip and a Patagonia design meeting scheduled to take place just outside the Valley. When we returned from our trip, we finally returned to finish our journey. We resumed free climbing at the base of pitch 6, where Katie was barely able to warm up before launching into the roof. I shouted words of encouragement as Katie climbed out to the lip of the roof, but she fell off while trying to climb around it. But after only a brief rest, she went back up and sent it! I felt a flash pump while following this pitch and barely managed to climb it without falling. I led up the last pitch feeling grateful for the fact that I had already free climbed it before the weather had gotten so hot. Katie followed the last pitch and continued up to the summit where were finally able to relax and join hands in celebration of the completion of our journey. A fantastic view with El Capitan standing boldly in the background, I was reminded of all the other climbs that could be done. There are always new possibilities, ways of improving, and something to be gained with each experience. Each generation learns from the previous one. I felt privileged to be a part of this process with Katie, who is still one of the most talented women I know. by Lynn Hill

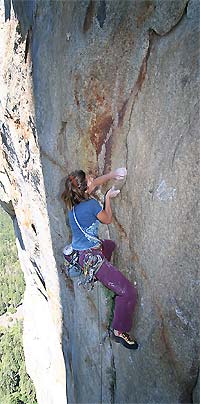

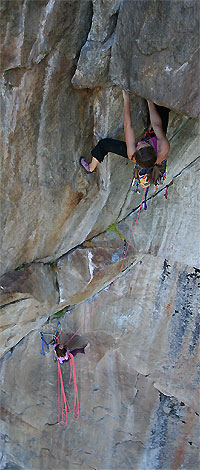

Photos: Lynn Hill on the 4th pitch. Below: Katie Brown climbing the roof. (ph arch. Lynn Hill) | ||||||||

Note:

Latest news

Expo / News

Expo / Products

25 Liter backpack with avalanche bag

Merino Wool Socks for Ice Climbing and Dry Tooling.

Revolutionary fast & light mountaineering boot SCARPA RIBELLE TECH 3 HD, with superior waterproof and breathable protection thanks to HDry technology.

Ocun Diamond S climbing shoes designed for maximum performance, comfort, and precision

Ferrino OSA 32, a backpack for freeriders and ski mountaineers providing maximum ergonomics and functionality.

The Zenith is a mountaineering axe that uniquely combines lightweight design with technical features for top-level performance.

Copia link

Copia link